Tech

Tech

Photography BY The author

Photography BY The authoran we talk about body fillers? White Star, Black Magic, if we go back any further we’ll be talking about lead. When we think of lead fillerwork today we’re likely thinking of famous ’50s customizers, or the same-era craftsmen of the autobody trade.

Bet you’re not thinking of autobody butchers. The ugly truth is: Before polyester fillers caught on, butchers used lead, too. I know because I’ve ground and melted liberal applications away for fresh starts numerous times during my own career.

Back in California, around the middle of the ’70s when I was, oh, in training, leadwork was still a part of Riverside Community College night school curriculum. But afterward, in the collision repair field, I can’t recall using lead one single time. Polyester fillers were improving, and by then insurers wouldn’t pay the difference for lead anyhow.

Granted, there are still some old-time craftsmen—no, let’s call ’em artists—who know how to lead. This story, however, won’t be about that, as we’ll be using fillers that are commonly used and available today.

With metalwork finished, as it’ll be, our 1955 Second Series Chevy project’s Unisteel cab is ready for necessary fillerwork. Having the truck mocked up as it’s been for so long makes it harder (at least for me) to focus on the little things. Lately, since we’ve been working on just a bare cab, we’ve backed up to weld up more cracks from old collision damage.

Only because it’s necessary, every cab panel will receive some degree of fillerwork. At this stage, the firewall is finished to 120-grit. It’s now covered for protection, and interior fillerwork is pretty much done as well. By taking this phase panel by panel, it should be a little easier to concentrate on details.

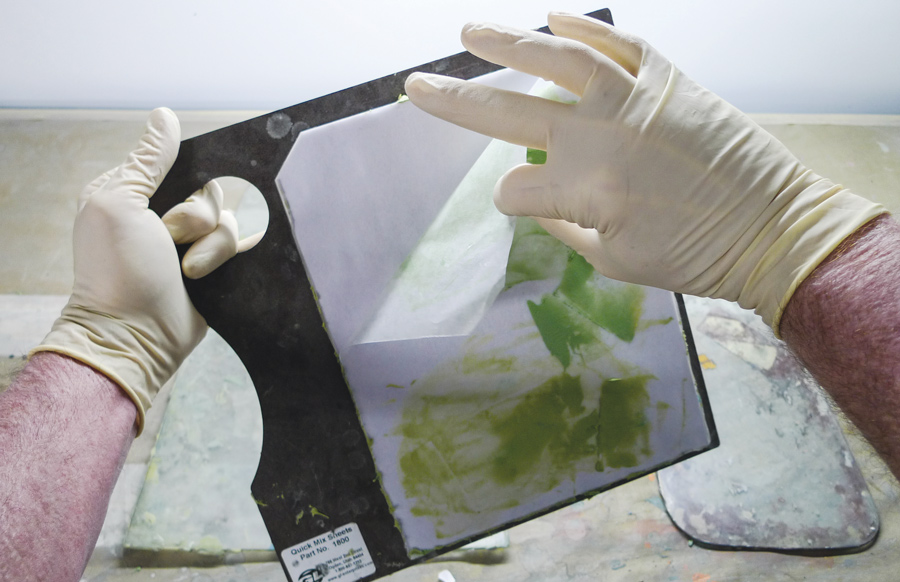

The next panel up will be the roofskin. Like the other panels, it’s taken its lumps and bumps. As a result of some obvious crash testing, the passenger-side roof pillars were both pushed forward. Making use of a Porto-Power, body clamps, and a ratchet strap, we corrected the affected pillars but afterward the roofskin seemed a little loose, as it would oil-can under pressure. Sure, we can heat and beat as necessary to shrink this sheetmetal as we were taught to years ago, but through modern chemistry we have a time-is-money option.

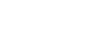

Today for body seams, patch panels, or wherever body sheetmetal has been welded, it’s good to begin fillerwork with fiber-reinforced filler. As polyester body fillers go, the fiber-reinforced variety is pert near structural once cured. Since this cab’s oil-canning roofskin will require the use of filler anyhow, beginning with fiber-reinforced filler could go a long way to stiffen the unsupported panel.

First things first, before we take a single smear we’ll need to prepare the steel. Before we do that, we’ll need to rid this cab’s crooks and nannies of remaining garnet blasting media. Back in Escondido, California, at Hot Rods & Custom Stuff (HR&CS), Zach the blaster did a bitchin job, as always. Of course there’s always trapped abrasive. Blowing, vacuuming, vibrating, rolling down the road in trailers, or rolling on a cab cart across the shop floor—all help to shake the stuff loose, but still, there’s more in there.

Earlier, along the way, we also discovered a crack in the passenger-side A-pillar’s factory-leaded seam. Our own instinct was to grind away lead and refill with fiber-reinforced polyester filler. Still open for suggestions, we called upon our go-to guru Dave Symcox of nearby Restorations Limited. When a job truly demands it, Symcox uses lead. We knew that, but we didn’t know the old-time factory lead is incompatible with the lead that’s obtainable today. Since remaining traces of the old may not mix well with the new, we’ll just go with our own instinct.

Here, as usual, there’s more than one way to achieve the end results we’re after. Today it’s a pretty common practice to apply a coat or two of epoxy primer ’tween prepared metal and filler. We do it here, too, but not every time. Since Montana winters are cold, and since our non-heated paint booth draws outside airflow, initial curing of epoxy primer wouldn’t be all that it should. Under the right conditions, epoxy primer is a good option. This time, quite fortunately, it’s not an absolute necessity.

If you’ve been with us for any length of time, you know we don’t downplay our mistakes. If you can learn from ours, you might not make as many of your own. This time we’ve set our own new record by making only one.

When preferred materials aren’t available locally, or when we just don’t like the prices, we’ll ordinarily call Summit. This time we drifted and sort of fell for a wannabe competitor’s fake free shipping offer. In the end we paid for that, as we waited, and waited, for higher-priced materials that arrived damaged—in an undamaged package.

One more thing, before we begin, let’s just touch on terminology. For the job at hand, the word “straight” should not apply. Task Force trucks, after all, are really rather shapely. With that in mind, let’s just use the words “fair” or “uniform” to describe our main objective. On that note there, let’s make us some dust, shall we?

For now let’s have a look and get the feel of what we’ve accomplished so far. In the final photo you’ll likely see telltale outlines denoting different applications. Although it might be slight, manual catalyst squeezes do tend to vary. That with time ’tween smears causes sanding rates to vary. We’ll cover that in our next installment—with a skimcoat application of resin-reduced Rage Gold.

SOURCES

SOURCES