teve Metcalf had wanted a 1955-1957 Chevy pickup ever since he was a teenager in Australia. Finding one became a lot easier when, in 2014, his engineering job for General Motors moved him from Down Under, where he’d worked for Holden, to the Motor City and GM’s proving ground outside of Detroit.

teve Metcalf had wanted a 1955-1957 Chevy pickup ever since he was a teenager in Australia. Finding one became a lot easier when, in 2014, his engineering job for General Motors moved him from Down Under, where he’d worked for Holden, to the Motor City and GM’s proving ground outside of Detroit.

It was about a year after arriving stateside that Steve found a 1956 stepside on craigslist and purchased it immediately. “It was pretty much original, but missing the gearbox,” he says. “After I got it home, I eventually dropped in a mild 355 small-block, a Powerglide, and a 10-bolt Posi, but left the original suspension as it was. After the first drive, however, the suspension was shot.”

Initial thoughts of making a budget Gasser-type hot rod evolved into expanding the truck’s all-around performance capability, especially when it came to handling. The project was relaunched at the start of 2017, with Steve dismantling the truck at home in his suburban two-car garage. Over the next 18 months—and with some spiritual guidance from GM colleague and Pro Touring pioneer Mark Stielow—the chassis and drivetrain were recast with 21st century performance elements.

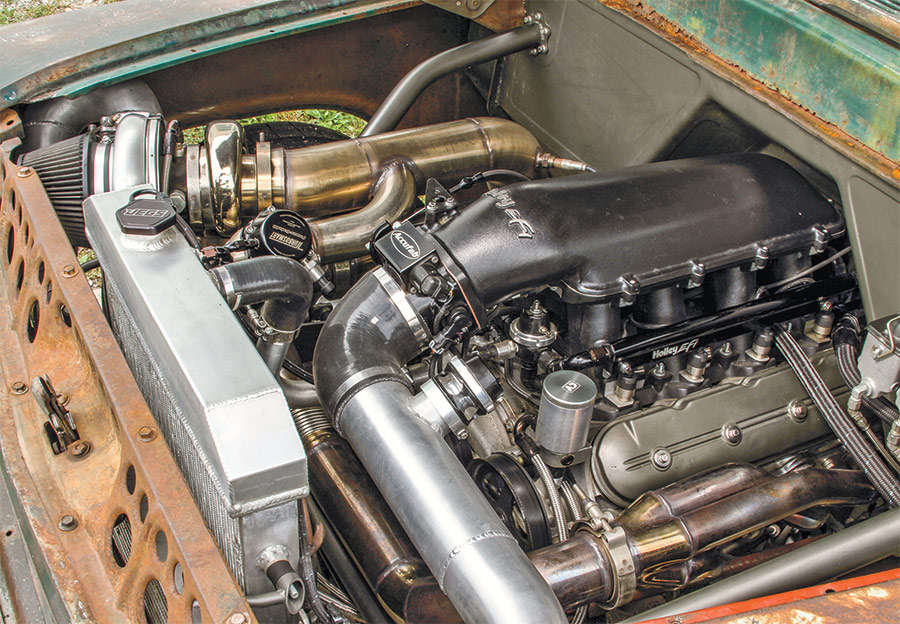

The old-school small-block wasn’t going to cut it any longer, either, as Steve eyed the performance capability enabled by a force-fed LS engine. The truck was going to get a thoroughly modern makeover under the skin, while retaining the sweaty, work-worn aesthetic of its six-decade-old bodywork.

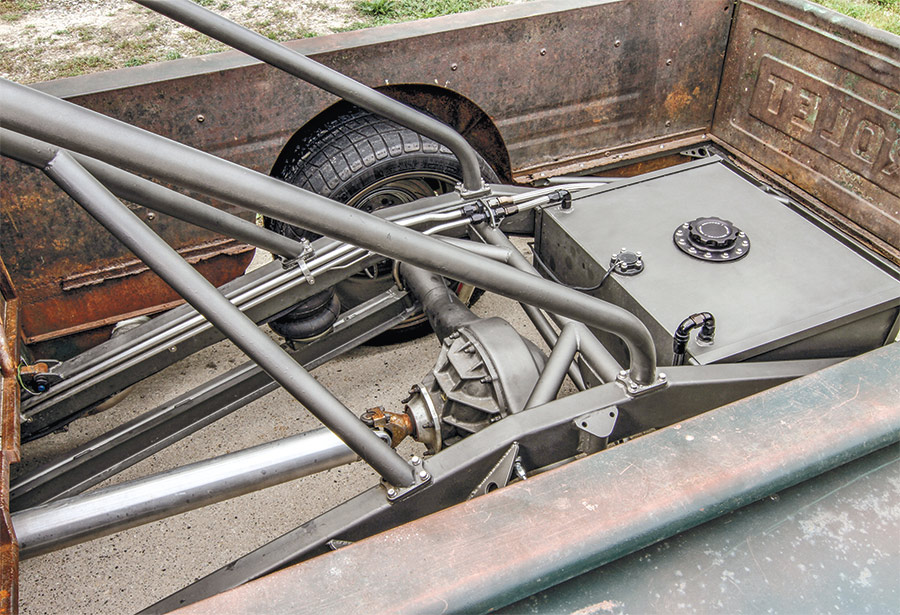

To provide further chassis reinforcement and driver protection, a 12-point rollcage was fabricated into the cab and it incorporated the mounts that attached the cab to the chassis. The front and rear sections were designed to interlock to allow easier cab removal.

“I didn’t have a frame table or anything like that,” Steve says. “It was all done with lots and lots of careful measuring.”

More custom fabrication was employed to hide a 4-gallon air tank, a couple of compressors, a wiring harness, solenoids, and more under the cab. There’s also an 18-gallon fuel cell wedged between the rear framerails.

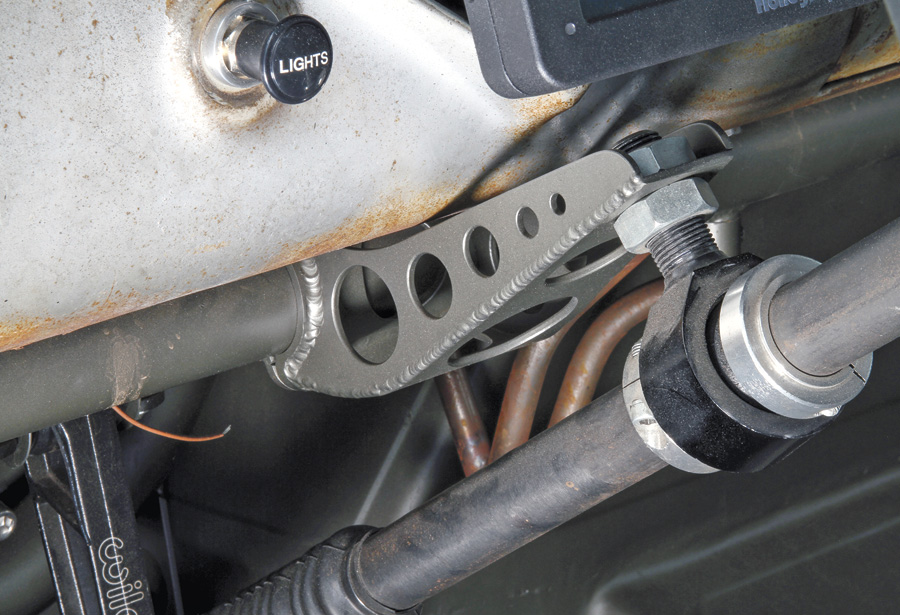

When it came to upgrading the suspension, Steve went with a custom-mounted C5 Corvette system in the front (with a beefy 1.25-inch-diameter Sprint car stabilizer bar) and a genuine NASCAR-type two-link design, locating a 9-inch axle, with TIG-welded 4130 chrome-moly truck arms featuring spherical ball joints. There are RideTech airbags and shocks at all four corners, too, which provide the desired slammed look while cruising or at a show, but enable easy, comfortable highway driving.

“It may seem counterintuitive to have an air suspension on a truck intended to run autocross tracks and dragstrips, but it works surprisingly well,” Steve says. “To be clear, I didn’t build this truck to be a class champion in any particular form of motorsports, but to be competitive and have fun trying the different types. To that end, it all works very well.”

“It’s a relatively mild setup these days, but one that gets the job done very well,” Steve says. “Overall, it was reasonably economical to build; and because of the comparatively high 10.5:1 compression ratio, I didn’t want to go too crazy with the boost. I’ll run it until it blows up and then I’ll rebuild it to take a lot more boost.”

The engine’s supporting details include a Holley High Ram EFI intake manifold with an Accufab 92mm throttle body, Holley 83-lb/hr fuel injectors, a custom intercooling system, a Turbosmart Raceport 50mm blow-off valve, Turbosmart Powergate 60mm wastegate, and, for the turbo itself, a Garrett GT4202R ball-bearing unit with a stainless steel TiAL exhaust housing. Some inexpensive turbo headers send exhaust to a diesel truck muffler under the cab.

With only the base tune from the controller, the truck makes more than 500 hp at the rear wheels. Steve believes there’s another 50-100 hp to be had with a finer edge on the calibration; for now, the truck runs great and pulls hard.

A Dodge Viper T56 six-speed manual transmission backs the pressurized LS6 and it is controlled with a short-throw shifter, custom billet extension (to fit the truck’s driving position), and a bronze-tone shift knob that was machined in Steve’s father’s garage, in Tasmania, Australia, halfway around the world. There’s also a McLeod RXT twin-disc clutch, an aluminum 3.5-inch driveshaft that came out of Stielow’s “Jackass” 1969 Camaro, and a 9-inch axle filled with a Strange centersection featuring an Eaton limited-slip differential, 3.50 gears, and Currie 31-spline axles.

The paintwork—or, more accurately, what’s left of it—is original, as far as Steve could tell when disassembling the truck. There’s rust and some filler in areas that has been left in place, while a replacement left-front fender was added, when filler more than an inch deep fell off of it. The front bumper was also shortened 2.5 inches to tuck it in closer to the body.

Steve shored up all the non-visible sheetmetal with discreet gussets that add reinforcing structure to the body. Also, the cargo box now has ball lock pins that enables it to be quickly and easily removed for chassis access and changing tires; and because he’s not a fan of the raised floor look of slammed trucks, Steve simply didn’t install a bed floor.

At a glance, the Spartan appearance looks simplistic, but the closer you look, the more the attention to detail in the fabrication reveals itself. The homemade rollcage, for example, carefully hugs the interior’s corners and incorporates mounts for the pair of Sparco racing seats, while most of the body’s reinforcing gussets have lightening holes that speak to the vehicle’s racing inspiration—and Steve’s fabrication skills.

“It was designed first and foremost to deliver on the performance requirements for the truck, but I also wanted the visible engineering details to look good,” he says. “Once you get past the time-worn body, there’s a lot more to see.”

That’s what makes the “NOTJUNK” personalized license plate particularly meaningful.

“It only had 600 miles on it when my mate, Bundy, from Australia visited,” Steve says. “We packed up and headed to North Carolina to participate in the 2019 Hot Rod Power Tour—a 2,200-mile round trip. Sure, there were a few teething issues, but we made the whole trip and the truck ran great.”

It included three days and three nights of driving in the rain with no wipers and no heat. It was adventure, for sure, but one he and his friend wouldn’t trade for anything.

“There’s a deep-rooted and enthusiastic car culture in Australia, but it’s something else in America,” he says. “Bundy couldn’t believe just how many highly modified classic cars and trucks are on the road in the States; and how the Power Tour was something that basically couldn’t happen in Australia because of a number of regulations.”

Steve continues to refine the truck’s performance and driveability, making it a better driver on the road and a stronger competitor on the track.

“Something like this with an air suspension isn’t supposed to work on the track,” he says. “It may not win the next Optima Challenge, but it’s a competitive vehicle and a blast to drive.”

Fair dinkum, as they say in Australia. And whether it’s there or America, the drive to build your own classic vehicle is the same; and Steve Metcalf is one of the fortunate few enthusiasts who’s been able to express his passion in both countries.

We’ll hold off on the other Australian puns and clichés to simply give a thumb’s up to a Down Under craftsman. G’day mates.