Tech

Tech

Photography by the Author

Photography by the Authorn the two previous issues of Classic Truck Performance, we documented installing C4 Corvette front suspension under an early Chevy pickup. Our intent was to build a ’52 Chevy 3100 series pickup that had the ride and handling qualities of a contemporary performance car, but like many projects there were complications to deal with—and in this case they were all of our own doing.

Our piecemeal pickup actually started life in 1952 as a 3800-series 1-ton truck. But as the cab and front sheetmetal is the same as a 3100 1/2-ton pickup, and this particular example was completely rust-free and in near-perfect condition, we decided to use it. Now all we needed to begin was a frame. As luck would have it our friend Gary Dagel, of Dagel’s Street Rods, had a ’55 frame that he would donate to the cause.

From the outset the plan was to install Corvette C4 suspension under both ends of the truck using kits from Don McNeil at Flat Out Engineering. McNeil specializes in kits to install ’84-96 Corvette C4 front and rear suspension components under an array of Chevy and Ford cars and trucks. These suspension components provide excellent ride quality with cornering and handling traits that turns a utilitarian pickup into a corner-carving performance vehicle. All Flat Out Engineering kits maintain the correct factory geometry, are known to fit like they should, and are designed to be easy to install.

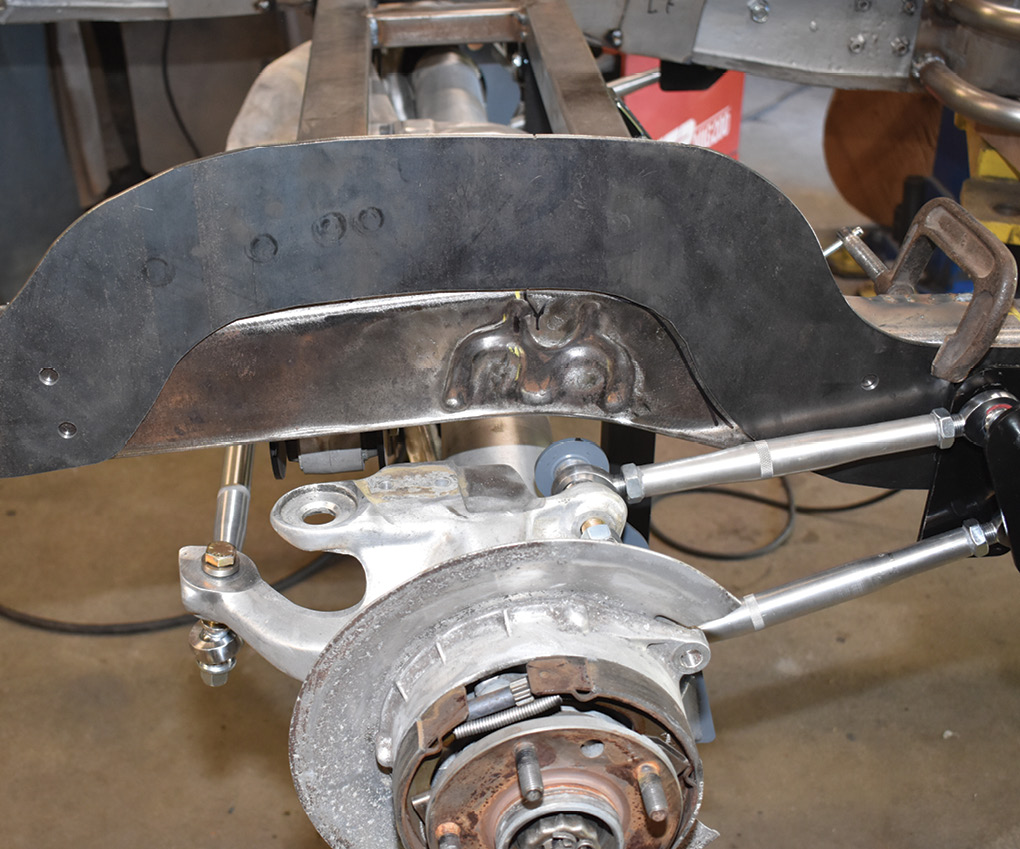

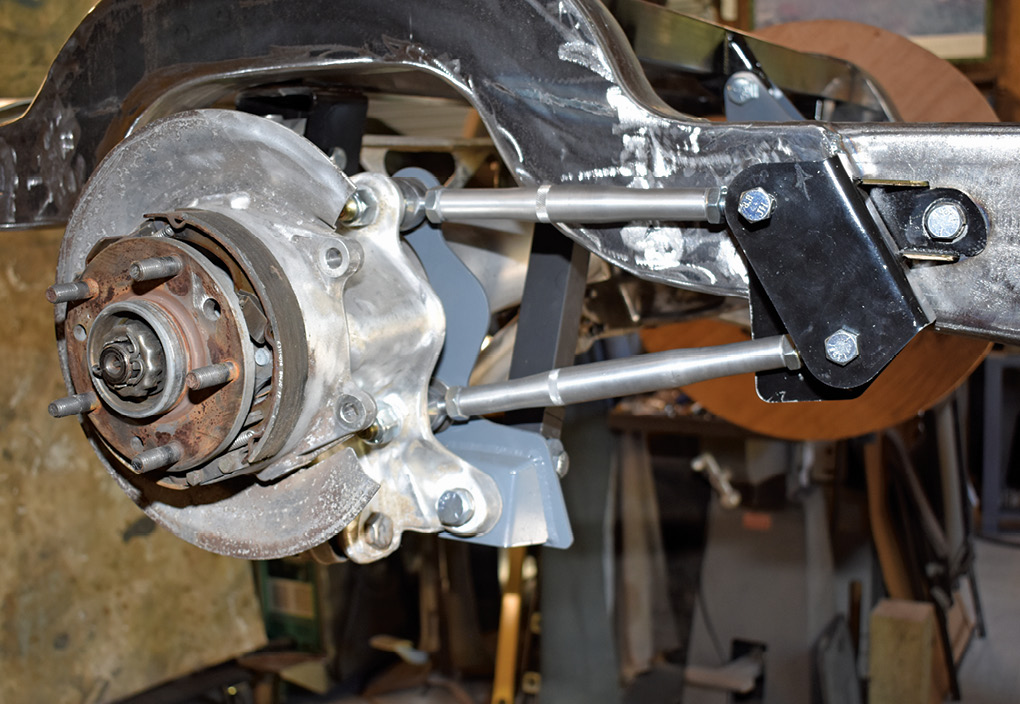

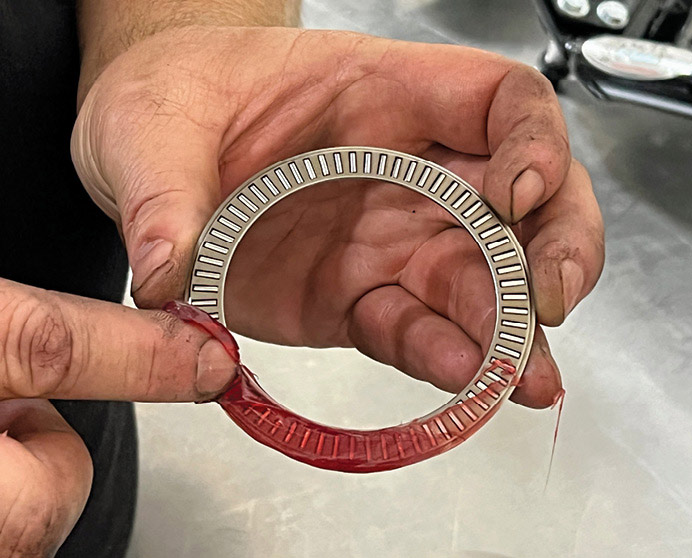

Once the front suspension was in place it was time to turn our attention to the rear of the chassis. There are two versions of the C4 rear suspension, ’84-87 and ’88-96. The early style is 61-1/2 inches wide (measured from front brake face to brake face). The ’88-96 is approximately 1-inch wider. The early series uses internal expanding parking brakes inside the rotor hats while the later design uses brake calipers with parking brake mechanisms. All C4 rears use aluminum suspension components and half shafts that are extremely strong while their light weight provides a sprung to unsprung weight ratio that is unsurpassed.

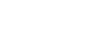

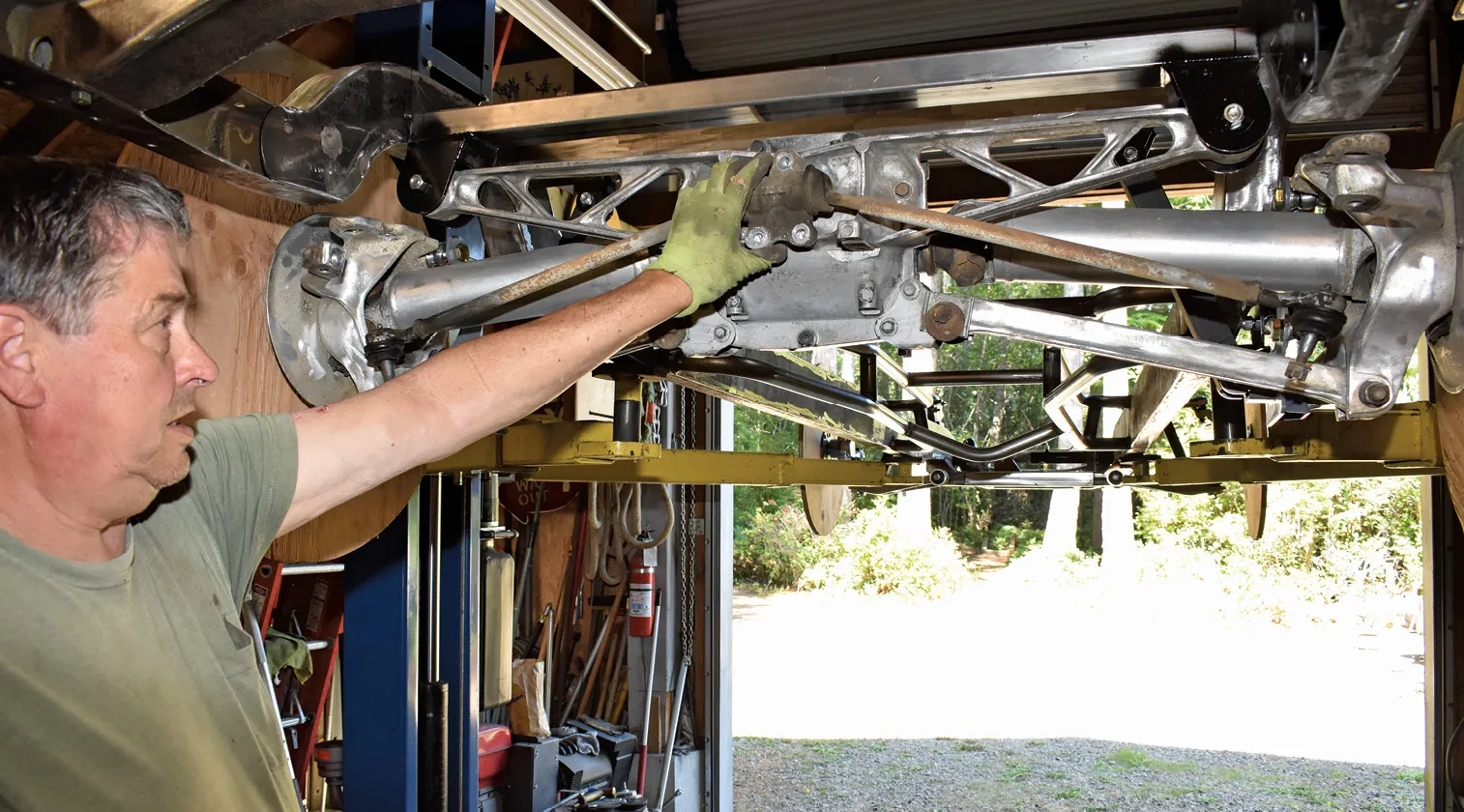

Installing Flat Out Engineering’s C4 rear suspension in ’36-53 Chevy pickups couldn’t be easier, as no major frame modifications are required other than adding boxing plates and welding the crossmembers in place. However, to get the ride height we were after and provide the suspension travel necessary our ’54 first series ’55 frame would have to be modified. After consulting with McNeil the decision was made to step the rear of the frame (thanks to Todd Hartman at Coyote Steel in Eugene, Oregon, who plasma cut four 10-gauge steel plates that were used to make the necessary modifications).

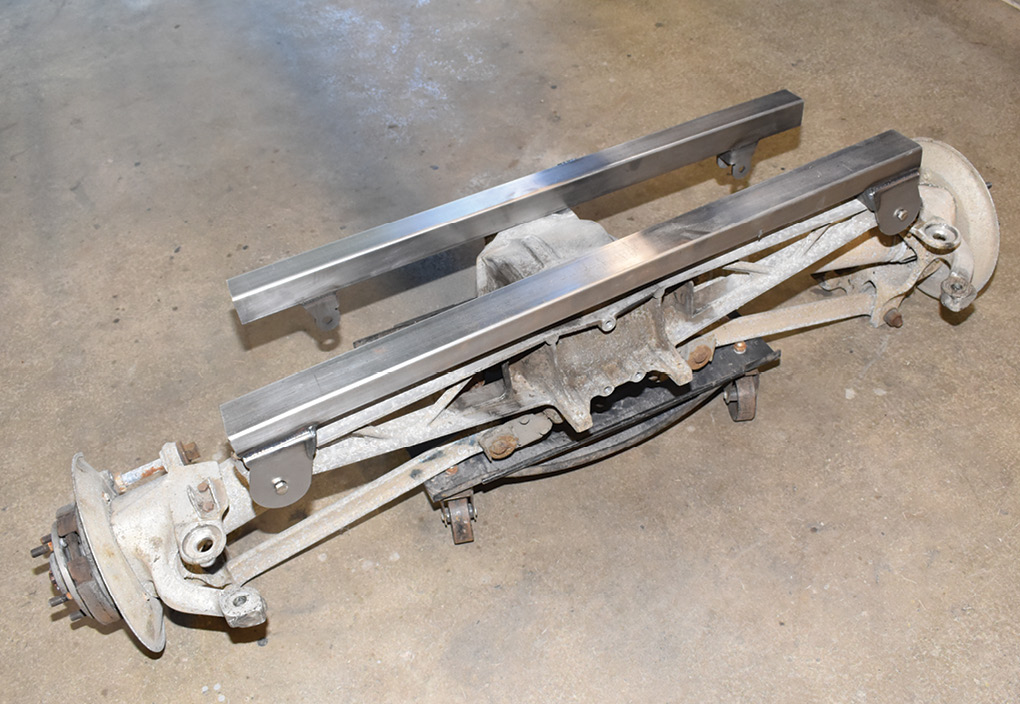

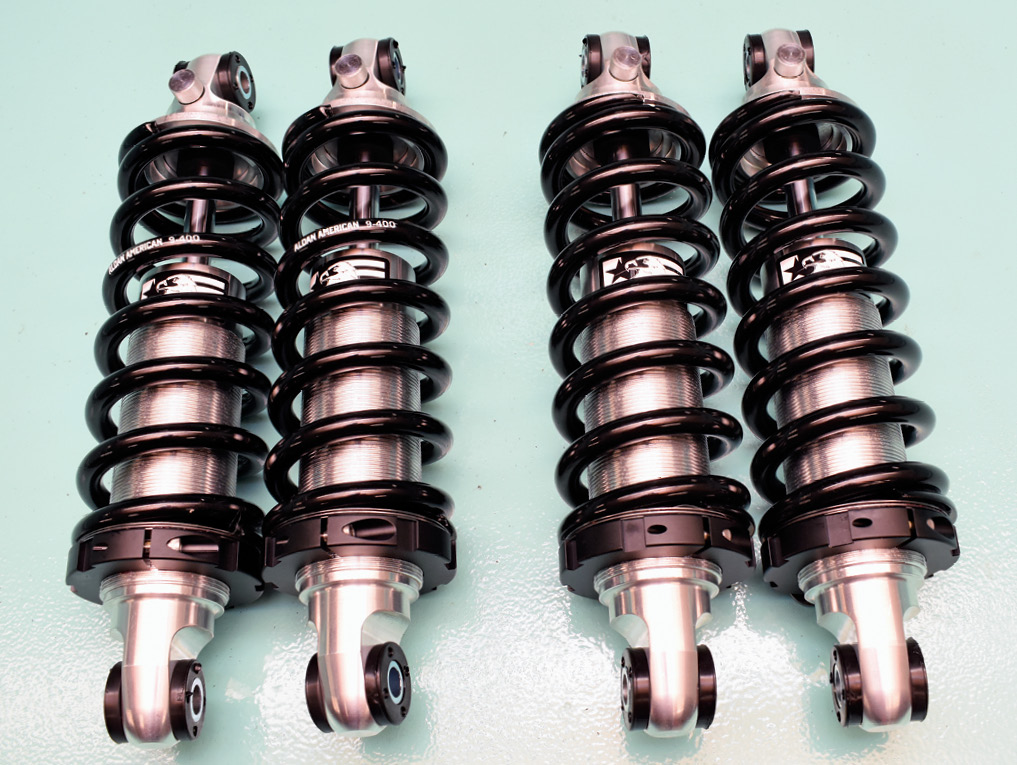

For a smooth ride McNeil has found that the Corvette carbon-fiber rear spring is too stiff for use under an early pickup, so his kits are designed to use coilover shocks. As McNeil recommends, we’re using Aldan coilovers. We also added Flat Out Engineering’s adjustable rear control arm kit rather than using the stock fixed Corvette components. In addition to adjustability the spherical rod ends in the Flat Out Engineering replacements eliminate the bind produced by the rubber or urethane bushings in the factory arms that inhibit suspension travel.

Another option we chose was Flat Out Engineering’s tubular rear toe bar kit to replace the stock Corvette assembly. The new toe bar links mount on the bottom of the rear hub assembly rather than the top as the originals did, thus providing additional frame clearance, which is needed with many lowered ride height applications.

We couldn’t be happier with the completed chassis or Flat Out Engineering’s installation kits. The decision to use a ’55 frame didn’t make any difference installing the front suspension. However, it did make the rear suspension slightly more challenging, but the finished product was definitely worth the effort. We’d have to say in this case the results definitely justified the means.

SOURCES

SOURCES