Tech

Tech

Images BY THE AUTHOR

Images BY THE AUTHORlumbing the brake system of a classic truck doesn’t require the use of exotic materials or methods and shouldn’t be a job beyond the ability of most DIYers. A few simple tools and a little bit of patience can yield some very nice results. We’ve covered the fancier side of things, installing a full stainless steel AN system on another C10 build we’re working on, but this time we’re going to shift our focus to the more common materials and techniques found at the local parts house.

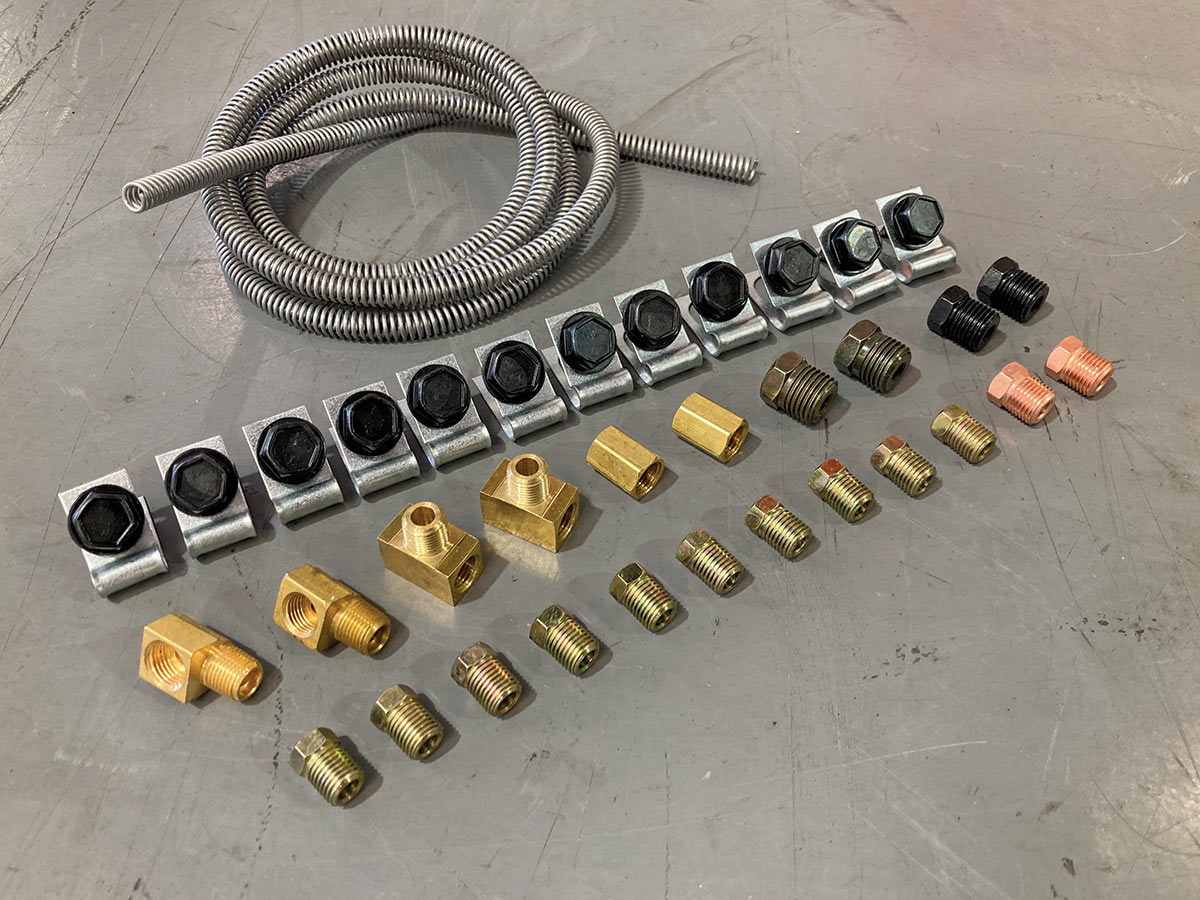

If you’re purchasing your brake lines and fittings from the parts supplier around the corner, chances are you’re going to be presented with few options. Brake line material will most likely be either steel or nickel/copper with fittings of the double-inverted flare variety. Both materials are fairly easy to work with, provide excellent resistance to corrosion, deterioration, and damage, and can be worked using standard hand tools. Steel brake lines, most of which are constructed using a combination of steel and copper with a protective zinc coating, have been the de facto standard since most of these trucks were new. More function than form, steel brake lines are easy to work with and provide excellent performance but lack the impressive appearance that stainless lines exhibit. Steel is also more affordable than stainless lines and components by a factor of about half. The use of nickel/copper lines, commonly referred to as NiCopp, has found an increase in popularity amongst both OEs and aftermarket companies due to its ease of workability (bending and flaring) and corrosion resistance. This makes it a popular material for the home builder as it bends easily using hand tools (or your bare hands!) and when properly treated, forms a double-inverted flare without splitting, cracking, or deforming without the use of a high-end flaring tool.

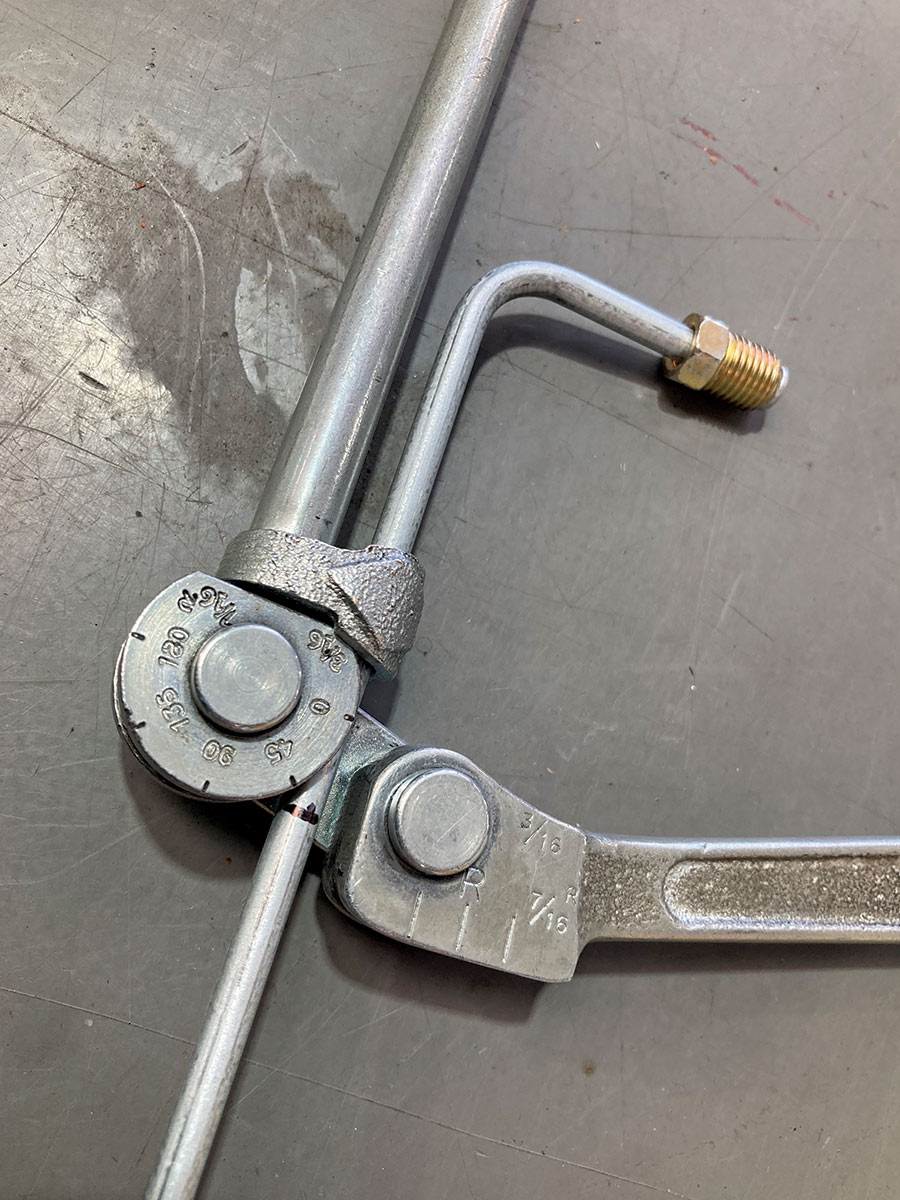

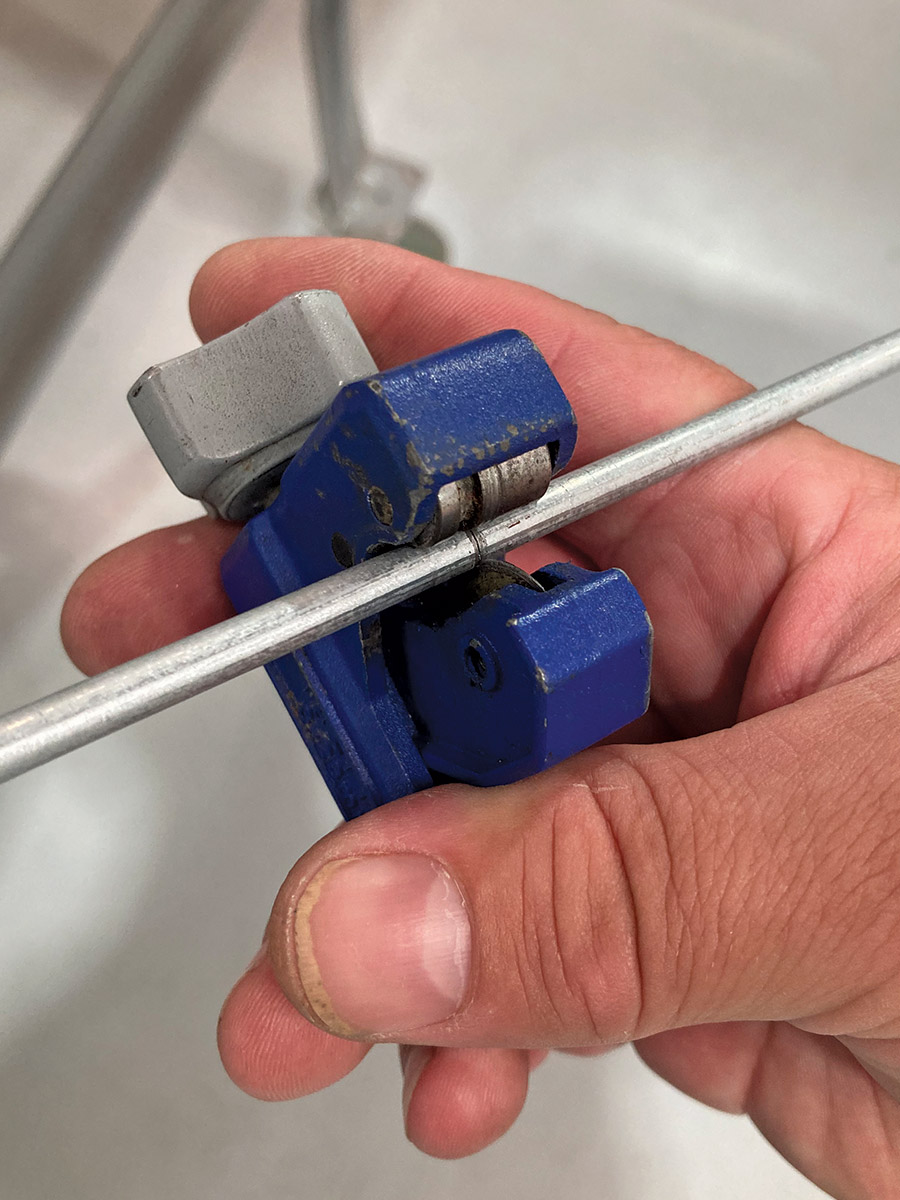

While a drawer full of tools makes for easy fabrication of a pro-level plumbing system, it’s not necessary. A decent bender and a good flaring tool can yield some surprisingly good results, both of which can be purchased over the counter from most auto parts shops. Personally, I prefer to make tight bends as opposed to sweeping, over-the-knee curves, so my bender-of-choice is one I scored at a swap meet that features a radius of 7/16 inch and is used for 3/16-inch lines only. Some jobs require larger radii bends, so it’s good to have a couple options when it comes to benders, but it’s not necessary.

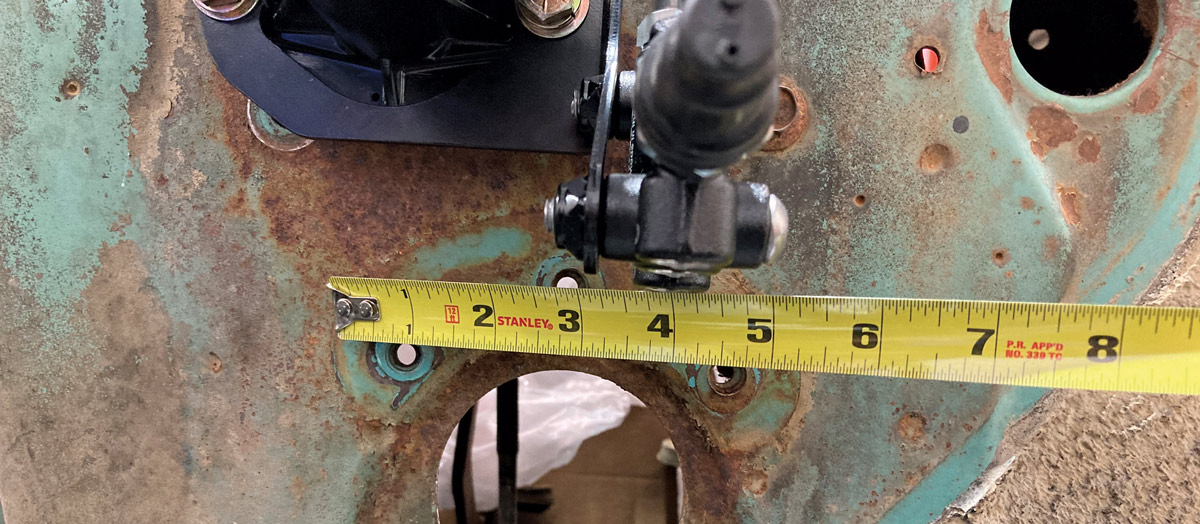

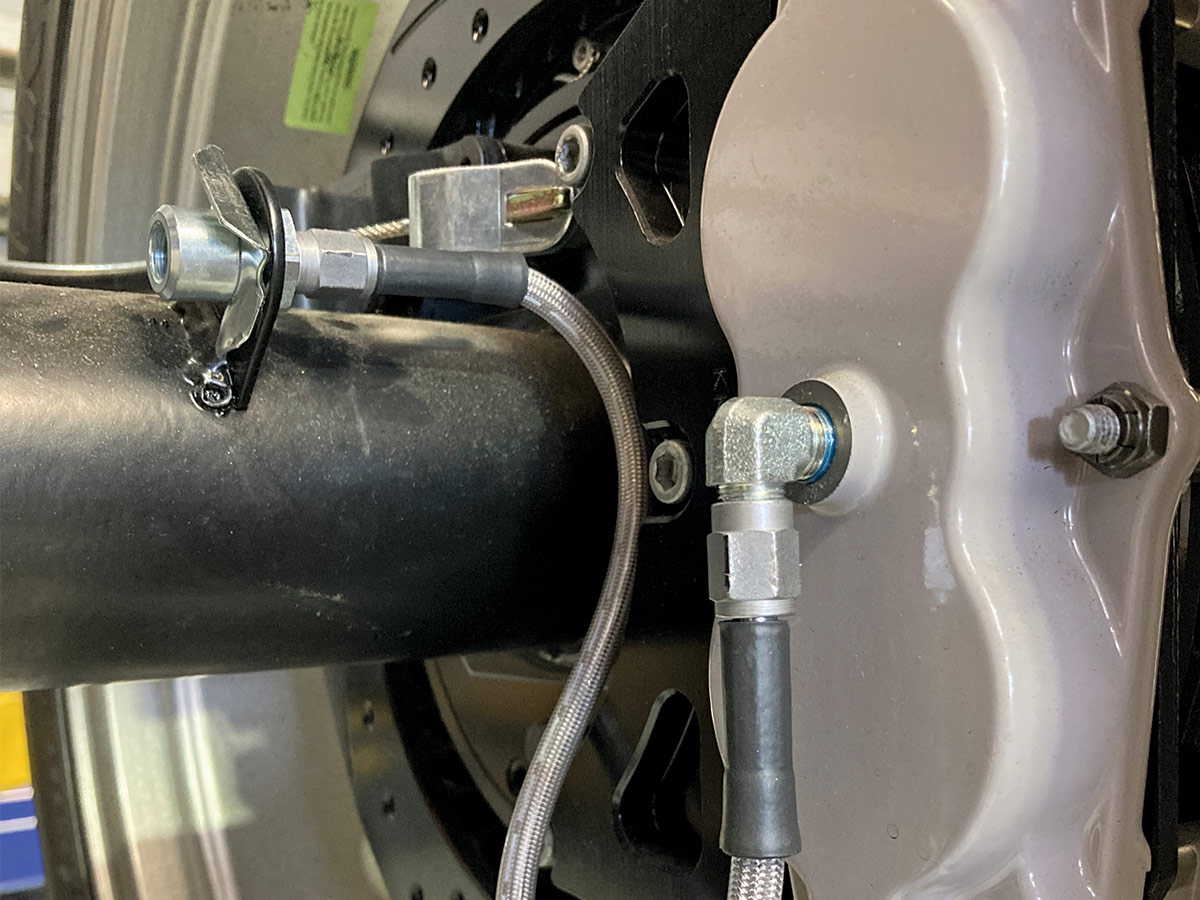

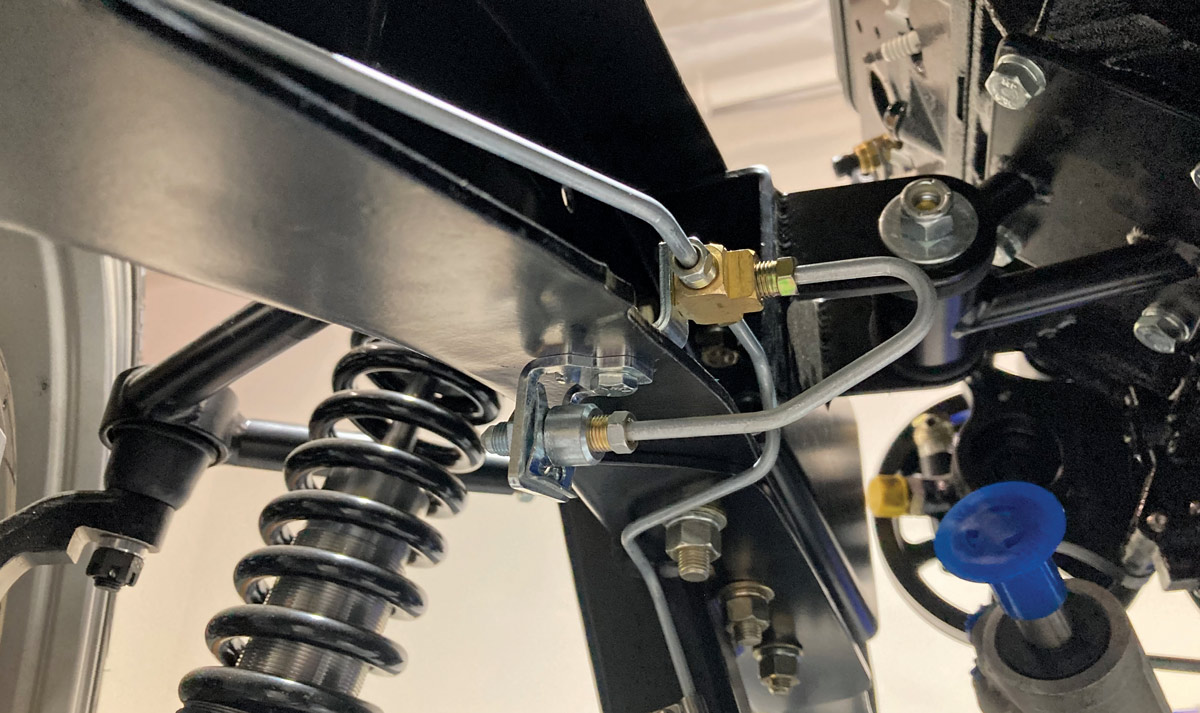

Fabricating a full brake system using a handful of straight sections of tubing can be a daunting task at first glance and might result in taking a second look at those pre-bent line kits that many manufacturers offer. But unless you’re restoring a truck with stock components, most of the pre-bent kits won’t provide a solution for every individual brake line. Our ’64 C10 build, for example, features a Chris Alston’s Chassiworks KP Components rear frame clip, Scott’s Hotrods ’N Customs IFS, and a Wilwood master cylinder and four-corner disc brake kit. All these custom modifications negate the possibility of using a pre-bent brake line kit based off stock C10 specs due to the drastic difference in chassis features.

Plumbing a brake system from scratch is a labor-intensive project, but not beyond the scope of most hands-on–type truck builders. A weekend spent bending and flaring lines can result in a very attractive system that looks as well as it functions. With the proper tools and a few good tips, anyone can plumb their project with ease!

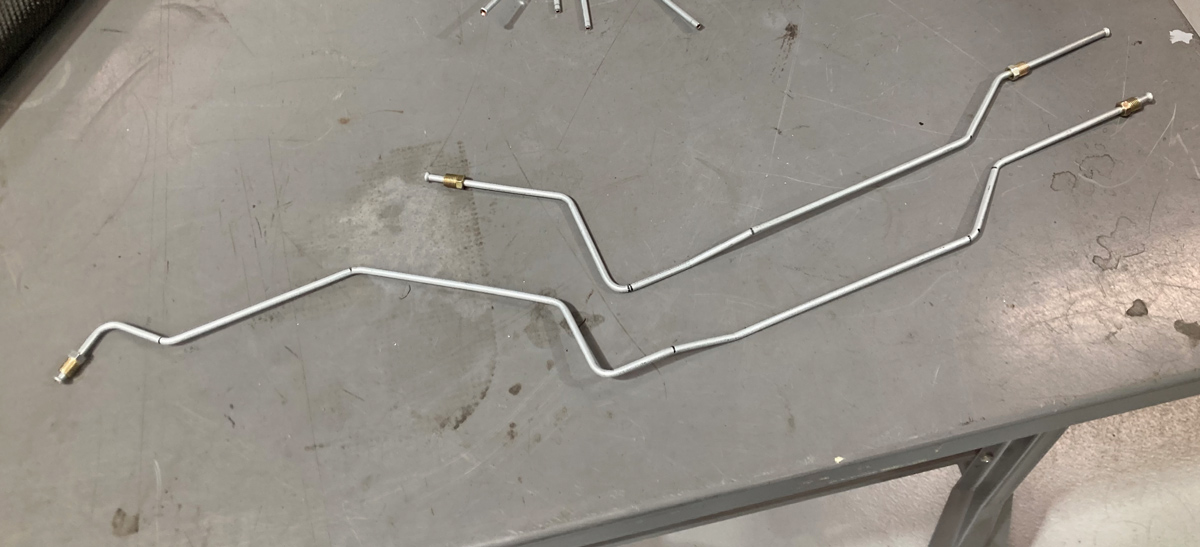

20. Here’s the finished hard lines for the rearend. Note the similarities of the brake tab side (right). Bending mistakes happen, but we can make lemonade from our lemons by setting an incorrectly bent line aside to either be used later at a different location or as a template for a similar bend. That pile of pre-bent hard lines is a small sample of “whoopsies” that I keep in my brake hardware drawer for situations such as these. Sometimes it’s easier to grab a section of pre-bent line, modify to suit, and then translate that to the larger line being fabricated.

SOURCES

SOURCES